March 11, 2004

300

This week sees the release of the final issue of one of the longest and most extraordinary comicbook series in the (admittedly short, unless we take the Scott McCloud approach and co-opt the Bayeux Tapestry and the Valley of the Kings) history of the form. Dave Sim's self-imposed life sentence on Cerebus is now officially over, and many murderers have got off more lightly.

If you aren't acquainted with Cerebus, you'll just have to take

my word for it that this is a big deal. (Well, not just mine, probably:

I imagine there will be dozens of other geeks blathering on about this

on the web this month.)

If you aren't acquainted with Cerebus, you'll just have to take

my word for it that this is a big deal. (Well, not just mine, probably:

I imagine there will be dozens of other geeks blathering on about this

on the web this month.)

There are a lot of reasons why this monomaniacal 26-year, 300-issue magnum opus is a landmark, and many of them are rather tedious: it's the longest sustained comicbook work ever, the longest run on a monthly comic by a single writer and/or artist (by a huge margin), the only time a (loosely speaking) single storyline lasting pretty much the whole lifetime of its central character has been published to a monthly schedule on this kind of scale. Ignoring the bonus strips, benefit pieces and guest appearances in the likes of Spawn and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, the body of Cerebus runs to 6000 pages.

And it's an amazing piece of work. In a good way, even, for quite a lot of its length. Those years of single-minded application gave Dave (all his readers are on first name terms) a mastery of the comics medium that is pretty much unequalled in the industry today. There are better writers, and better artists, but in terms of sheer cartooning expertise, Dave Sim is -- or rather was -- the shit. In the truest sense, Cerebus is a masterpiece.

Of course, every silver lining has a cloud, and in this case it's a fucking doozy, a skyfull of black, crackling thunderheads, lowering from horizon to horizon. Oh dear me, yes.

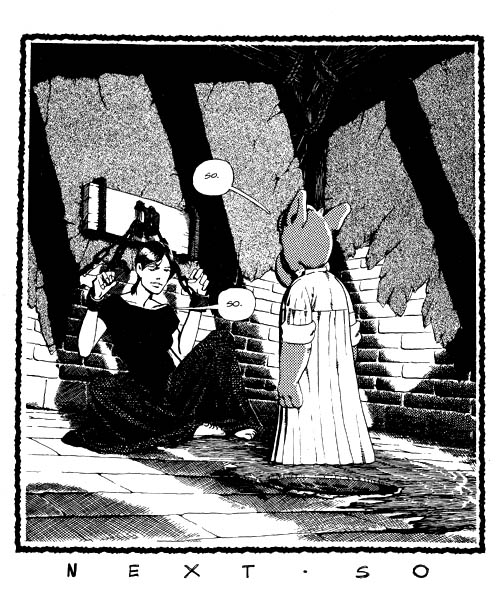

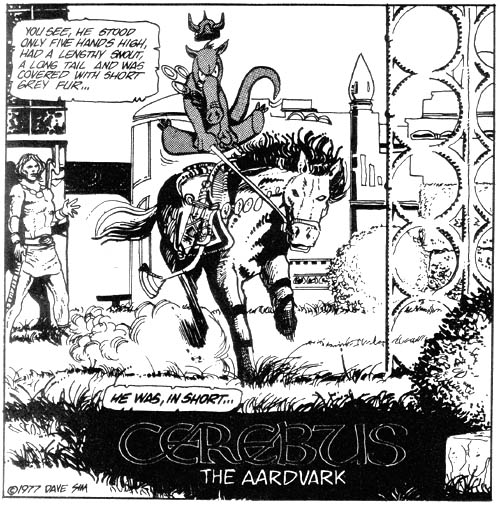

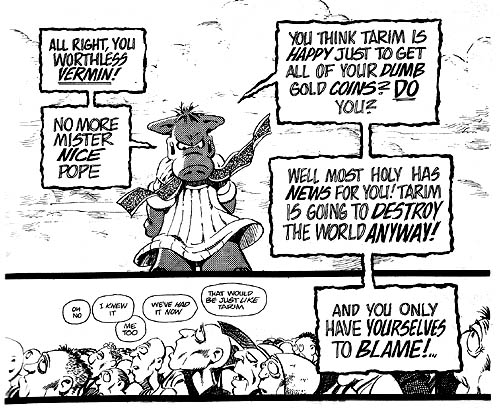

Cerebus the Aardvark hit the scene more than a quarter of a century ago, and he was a very different beast from the one facing the final curtain this week. The image above is his arrival in his own comic (I believe he'd made an appearance or two before this in backup strips somewhere, but all that was before my time).

Cerebus started out as a (seemingly disposable) parody of sword and

sorcery fantasy comics in general and Barry Windsor-Smith's tenure on Marvel's

Conan the Barbarian in particular. An independent "funny animal" book

long before the turtle-fuelled boom of the late 1980s, it was disconnected,

episodic and fairly clumsy. The gags were fast and cheap, and some of them

were very funny, but it was unexceptional stuff, the sort of thing you'd find

in an above-average fanzine or student newspaper.

Cerebus started out as a (seemingly disposable) parody of sword and

sorcery fantasy comics in general and Barry Windsor-Smith's tenure on Marvel's

Conan the Barbarian in particular. An independent "funny animal" book

long before the turtle-fuelled boom of the late 1980s, it was disconnected,

episodic and fairly clumsy. The gags were fast and cheap, and some of them

were very funny, but it was unexceptional stuff, the sort of thing you'd find

in an above-average fanzine or student newspaper.

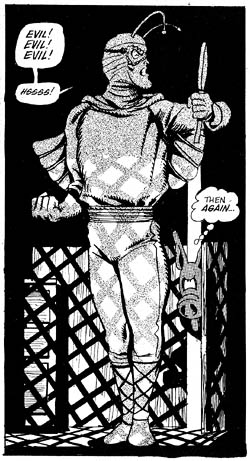

An awful lot of things from those early stories would be picked up and retrofitted into the grand design later, making them an unavoidable part of the complex, self-reflexive whole. Slapstick parodies like Elrod and the Cockroach became an integral part of the Cerebus storyline, turning up again and again, accreting intricate layers of significance that give the work a great deal of textural richness. The downside is that they tie everything back to those clunking first issues, in which barely a hint of the later sophistication can be discerned.

For new readers this is a bit of an obstacle: either you start at the beginning and wade through a lot of unconvincing ho-hum comics, or you arrive somewhere in the middle with no fucking idea what's going on. Seventeen or so years ago, the beginning wasn't even in print, so I had no choice but to start out bewildered.

Although I'd had various bouts of reading them before that, my Damascene conversion to grown-up comics geekdom came with Dave Gibbons and Alan Moore's seminal dystopian fantasy Watchmen, which remains (IMHO) a high point in graphical literature to date. Thanks to a mention in, of all places, The New Statesman, I started on this just after issue #2 came out, when #1 was still prominently on the shelves at Forbidden Planet (the original seedy Denmark Street shop, mind, a far cry from the sterile supermall of today). It was... a revelation. Eventually I would read enough to be able to put it into context, but at the time its darkness and detail seemed unprecedented. Other titles -- The Dark Knight Returns, Swamp Thing, Love and Rockets -- quickly joined the shopping list, and I was hooked.

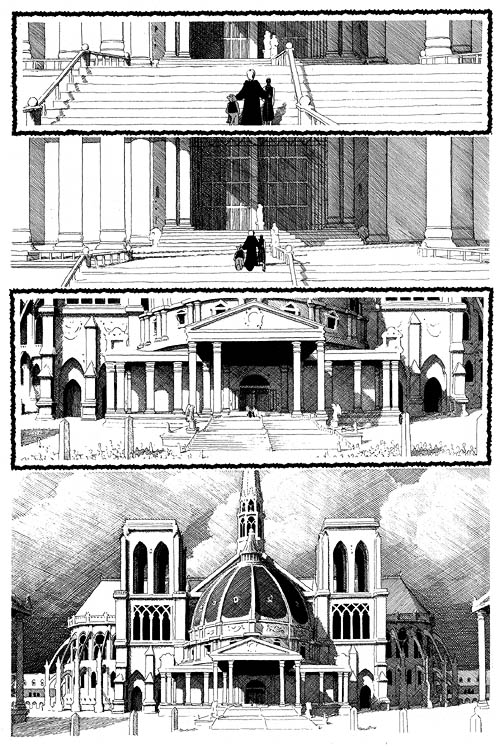

Things seemed to be really happening in comics at that time, and one of those things was Cerebus. God knows what drew me to it in amongst all the other dayglo tinsel -- probably its monochrome sobriety as much as anything -- but questing around for something else to give me that "intelligent cartoon" buzz I lighted on (I think) issue #87. It was right in the middle of the wacked-out, baroque Church and State story arc, which verges on the incomprehensible even when you have the whole picture. As a newbie, I found it entirely baffling -- and irresistible.

It took a few issues to start getting to grips with what seemed to be going on. I still had no idea of who most of the characters were and how they might fit into the story, but I could appreciate the artistry and wit involved and the incomprehensibility just added to the fun. The idea that this was going to run, month in, month out, until 2004, that some of what was going on might not be explained for that long, was pretty appealing in a masochistic sort of way. The book's letter column was filled with people saying "With you till 300" and I thought, yeah, why not? I can commit to another 17 years of this.

With you till 300, Dave.

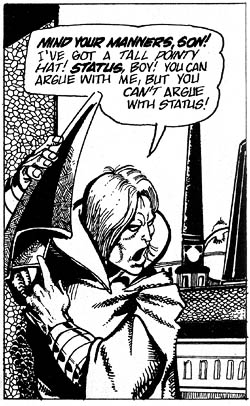

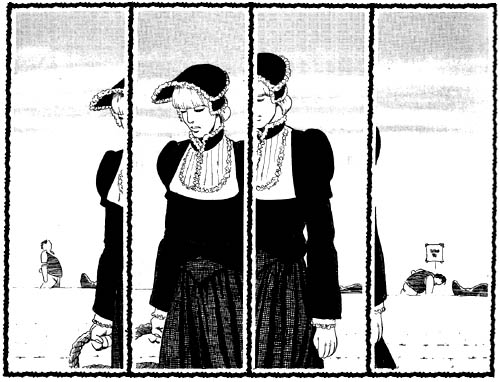

Gender issues were already featuring significantly in the comic, and Church and State concluded by presenting an oddly-sexual cosmology, but things were still relatively even-handed. Dave occasionally made broadly anti-feminist remarks in the back pages, but these were quite easy to ignore, especially when set against a storyline that could easily be read in feminist terms and strong, complex, nuanced female characters like Jaka and Astoria.

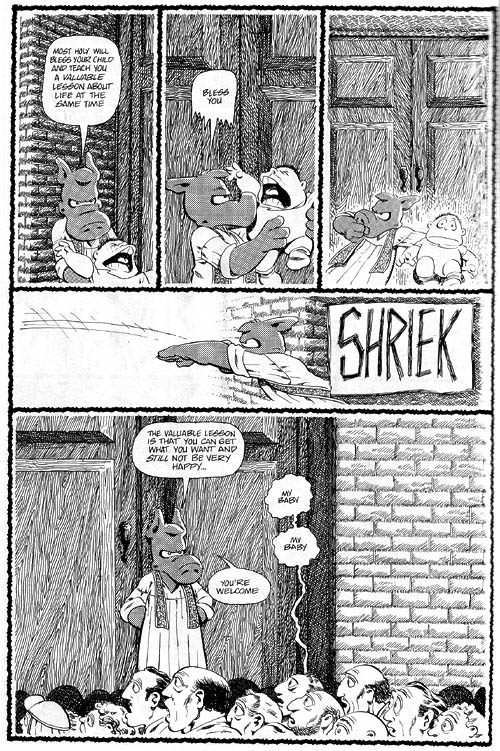

After an apocalyptic showdown, Cerebus shifted into a much quieter, gloomier register, and the title character was radically sidelined for most of the next 3 years, barely appearing from one issue to the next. Dave's formal experimentation came to the fore, and readers started falling by the wayside, bemoaning the lack of jokes. But despite weaknesses in the prose sections that were now being woven into the comic, the slow burn of Jaka's Story packs quite a punch, and Melmoth, though weaker, has an authentically grim, morbid quality that is quite affecting in the end.

With half the 300 issues under his belt, and having had a good long stretch

focussing on minutiae, on the mundane and ordinary, on human relationships,

Dave began the second ("female") half of Cerebus, and things got

simultaneously better and much worse.

With half the 300 issues under his belt, and having had a good long stretch

focussing on minutiae, on the mundane and ordinary, on human relationships,

Dave began the second ("female") half of Cerebus, and things got

simultaneously better and much worse.

The 50-issue Mothers & Daughters sequence is so recklessly complicated, so fast and furious, that at the rate of 20 pages per month it was hard to make sense of at all. In a headlong rush over more than two years, nearly everything that had happened previously, including all those early, disjoint barbarian hack and slay episodes, was thrown into the blender. All the old storylines and all the old mysteries were juggled and revisited and stitched back together to mean something different. Much of that is really an astonishing tour de force.

Sadly, it's also the point where Dave himself becomes harder and harder to avoid. Dave the creator. Dave the ideologue. Dave the Evil Misogynist.

In the third book of Mothers & Daughters, "Reads", Dave steps out of the shadows. Just as the storyline hits fever pitch, Dave slams on the brakes, and everything gets bogged down in long and clunky prose pieces, starting out as the story of a fictional writer in the Cerebus universe, but then shifting to autobiographical pieces about Dave himself (under the nom de plume Viktor Davis), and eventually to a tub-thumping exposition of his theory of life, based on a curious inversion of the cosmology presented at the end of Church & State.

Women, Viktor tells us, are voids, bottomless pits of emotional need, who exist to enslave men. Men are burning fountainheads of creative energy that women latch onto and leech off of. Men surrender their individuality for sex and comfort, the kiss of death to any artist.

And so on. And on and on and on and fucking on.

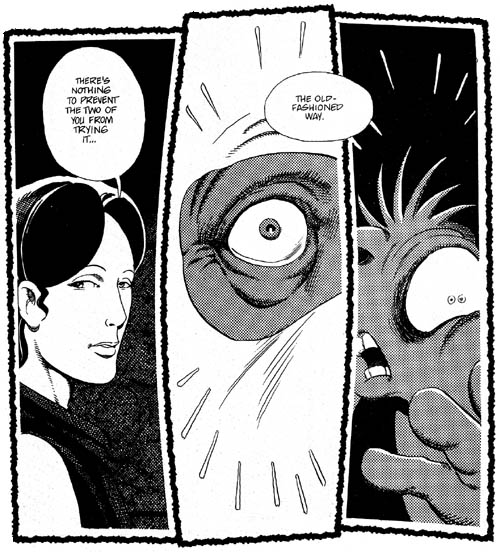

A couple of issues earlier in this extended discussion, Viktor revealed that there would not be 300 issues of Cerebus after all. He'd planned for 14 years to stop at issue 200. He had kept the secret all this time, in anticipation of the day when he would reveal his deceit and give all his readers a bit of a shock.

A little later, he retracts. Probably.

The reader and Viktor Davis regarded one another for several minutes, without speaking, across the strange, lighted rectangle. Calmly, Viktor Davis withdrew his pack of cigarettes from his hip pocket and selected one. Raising the lighter in his right hand, he lit the cigarette in a quick, easy motion.

"What's the matter?" he asked, still smiling through a dissipating cloud of smoke.

"Don't you trust me?"

Interleaved with this interminable dissertation, the Cerebus storyline struggles to maintain its momentum. There's some talking, and a big fight scene. Dave insists that the comics story and the prose pieces in Mothers & Daughters are saying the same thing in different ways, but I defy anyone to read it that way. The comic strip remains subtle and thrilling, light years away from the misogynist ravings in the text. Astoria's philosophical departure doesn't chime in the slightest with Viktor's anti-feminist screed.

At the end of "Reads", Viktor and the reader part company, and the story resumes. If you skipped over the Viktor Davis text pieces, you'd be none the wiser. The next and final book carries the story to a mostly satisfactory conclusion; many things are explained; a resolution of sorts is achieved.

Dave inserts himself into the narrative again, but in a way that, in the terms of the comic, makes some kind of sense. (He also acknowledges a longstanding debt to Warner Brothers cartoons, with particular reference here to Duck Amuck.)

Mothers & Daughters wraps up at issue 200.

The thing is, Viktor Davis wasn't kidding after all. To most intents and purposes, Cerebus ended at that point.

Being the stubborn type I am, I stuck with the "little grey bastard" for another 6 years. I wasn't going to abandon the 300-issue project just because its author turned out to have some pretty distasteful views. Plenty of artists have had distasteful views, it doesn't invalidate their work. And Dave's artistic self seemed strangely out of touch with his professed misogyny.

But two things had changed.

But two things had changed.

The first was that, basically, he'd run out of story. He presumably had some plan for where to go from this point, and perhaps he even stuck to it. But for the most part it was shapeless and rambling because all his points had been made, all his narrative tricks and long-term groundwork had been used up.

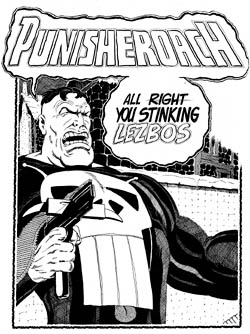

Casting around for something to fill that void, it seems to me, he settled on himself. The role of the marginalized freethinker in a world of suffocating political correctness, which he'd adopted in the latter stages of Mothers & Daughters, fit him nicely. Having nothing interesting left to say within his world or his characters, he chose instead to turn them into a channel for his meandering obsessions.

The second thing that changed was that he found God.

Now that's the kiss of death to any artist.

As the years passed, the pages of Cerebus became more disagreeable, more tiresome, more bible-bashing and more cantankerous. I continued reading it anyway. Each issue seemed more of a chore, but I'd made a commitment, if only to myself. The spectacle of a once-great cartoonist descending into rambling senility was disheartening, but in some way true to life. Due to a distribution mix up, I wound up reading a few issues out of order -- it was barely possible to tell, much less care.

Wading through Dave's notorious Tangents essay in issue 265, I was, yes, outraged and offended, but much more just weary of the whole thing. Even then, I thought I'd be there until the end.

Well, I was wrong. As it turned out, I just lost interest. I realized I was only buying the thing out of sheer bloody-mindedness. I missed an issue, and didn't miss it. With just two years to go before the magnum opus was completed, I stopped buying it. Life's too short.

Today, for sentimental reasons, I bought and read Cerebus 300. I intended to scan in a panel or two and finish this entry with that, but honestly I can't be bothered. It's distantly interesting, but I'd rather stick with the work of a great comics creator at the peak of his powers and forget the grim shade he turned into.

In the last couple of weeks I've re-read the whole run to issue 200, skipping only a few of the prose pieces from "Reads". It's an experience I can heartily recommend to anyone.

As is the experience of knowing when to stop.

Posted by matt at March 11, 2004 07:27 PM

Masochist :) Posted by: Stairs at March 11, 2004 08:06 PM